Epistemic status: Reaction

Oh wow, Jeremy Howard left the US because it "isn't really the right place for us to raise a family". I know what he means... My first thought was, "Oh, I'll miss him". But I live on the East Coast, so it's not like I'm much less likely to meet him now. Also that man is so prolific there's little chance his move will reduce his influence on my engineering life.

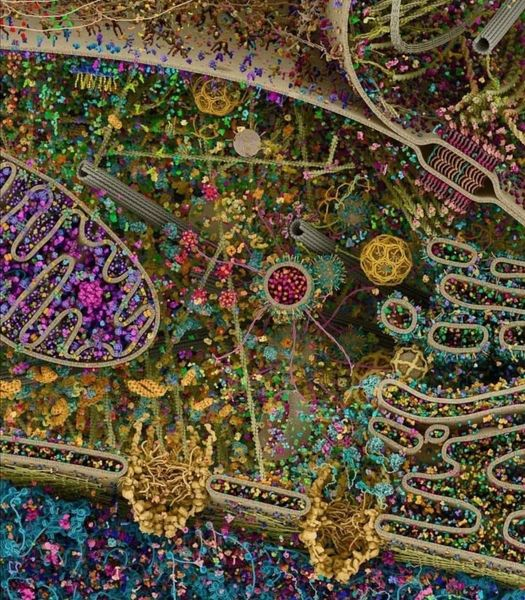

Cells and nanotechnology

Epistemic status: This picture was initially presented to me as an electron microscope picture. Turns out it's a rendering in Maya based on EM pictures, which doesn't affect what seems to me to be a common sense conclusion.

Reactions, in order:

- Wha... what??

- Kinda crowded in there

- Wait, cells really look like textbook diagrams of cells? [Maybe, maybe not. This picture is a rendering. My wife also mentioned that even if it was an EM picture, the colorization would highlight things we already know about, and ignore what we don't know about.]

- The delay in practical nanotech fabrication methods have (afaict) caused the public impression of them to be "this is fake, and you're weird to talk about it". But pictures like this remind me that's wrong. Nanotech is a real, utterly life-changing technology that will one day give us godlike powers, because tiny machines already exist. We just can't yet build our own.

Common sense exists

Epistemic status: Preliminary thought that didn't fit in a tweet

I know at least one person who doesn't believe "common sense" is a real thing. I disagree, in the sense that within a given culture, there exist a pool of beliefs and a pool of epistemic operators that are approximately common knowledge, so when you present your neighbor with some new fact, it's approximately common knowledge between you two that they will make all of the obvious (1-step) inferences from the pool of beliefs plus the new fact, using the pool of epistemic operators. Maybe they won't do this instantly or automatically, but if you can assume they're motivated to think about it, they'll draw at least some predictable conclusions. I call the pool of shared operators "common sense", and the inferences "common sense beliefs".

Note that I'm using "common knowledge" here in the technical sense that, e.g., two parties Alice and Bob know what each other knows, and they each know that each other knows, and they each know that each other knows that they know, etc., etc., ad infinitum. It's approximate in two senses: parties are computationally limited so they don't actually have infinitely recursive common knowledge, and the individual facts about which they have this approximate knowledge aren't exactly the same between them. The practical effect is the same though. I can be pretty sure, for example, that if you're reading this blog post you know English. I also know that you know I know that. And I can be pretty sure you know that I know that you know that I know... Seems crazy, but helps us make unconscious inferences we would be otherwise unable to make.

Anyway, here's a sketch of an argument for the existence of those two pools: Because we all have biologically pretty similar brains and homogenizing public schools followed by consumption of the same social-reality-creating major media outlets seem likely to produce a pool of common knowledge. We can have common knowledge of certain inferences "everyone" will likely draw from the knowledge commonly available to everyone again because our brains are pretty similar, and because if there weren't such a pool I don't think we'd even be able to have a conversation in the first place: We wouldn't even know what lines of argument to suspect others would find cogent.

NB: I'm not saying everyone will agree on what's common sense, only that they'll mostly agree. I'm also not saying that they'll agree what lives in each of those pools, only that they'll mostly agree. I'm also not saying that more well-informed and well-trained people don't have larger pools - they do - though I'd expect they still have common knowledge of

Magic: The Gathering is Turing Complete

Epistemic status: Comments I wrote for my journal club while reading a paper

The Decipher Journal Club is reading Magic: The Gathering is Turing Complete this month. In the spirit of the all-comments-public experiment, I'm posting a bit of commentary I wrote to the other members while reading the paper.

Some helpful/funny notes in here as I read the paper.

- If you don't know what a Turing Machine is, I'd recommend just watching the first few videos on YouTube about it.

- They're relevant because a ton of important things have been proven about them, and if you can "embed" a Turing Machine into something, it means many of those theorems apply to whatever you were able to embed it into.

- "Embedding" means just arranging a subset of the rules of your system such that they simulate the workings of a a Turing Machine.

- A "Universal" Turing Machine is a special case of a Turing Machine that can simulate other Turing Machines, which is to say, it can perform any computation that any computer can perform, given the right inputs.

- So if you can embed a Universal Turing Machine (UTM) into your system, it means that your system is capable of simulating any other computer, and can perform any computable task.

- "Rogozhin's UTM(2,18)" refers to a Turing Machine with 2 states and 18 symbols, which Rogozhin proved was universal. It's a pretty compact Turing Machine, which is likely why it was selected to be embedded into Magic.

- I'm a bit confused about their construction. Cleansing Beam doesn't do what they say it does, and at the moment I can't see how Coalition Victory helps them change the state. I also notice that both Rotlung Reanimator and Xathrid Necromancer are 2/2 creatures, so they're going to get killed by Infest unless they're modified. We'll see if that clears up as I move along. [EDIT: Yes it does.]

- OK, wow. They didn't typo by saying Cleansing Beam. They deal with the fact that that card deals -2/-2 to a target creature and all creatures of the same color (instead of what they were claiming it does, add +1/+1 to creatures of that color) with a dizzying array of spells: Privileged Position, a hacked Olivia Voldaren, hacking all Alice's creatures to be of type Assembly-Worker, Steely Resolve, Illusory Gains, and Vigor. So yeah. Sheesh. Ultimately, they end up putting two +1/+1 counters on the side of the tape they're moving away from, and a -1/-1 counter on all creatures representing the tape, which has the intended effect of updating the tape position representation. I assume the convoluted nature of the operation is because Magic doesn't have a direct way of adding +1/+1 counters to all creatures of a particular color, but let me know if you know otherwise.

- I love "To ensure that the creatures providing the infrastructure ... aren’t killed by the succession of −1/−1 counters...". This section also takes care of my objection from earlier about the "creatures providing the infrastructure" being small enough to die from the earlier steps, though my specific objection at the time was handled by the Privileged Position.

- "D. Changing State" was a bit hard to follow, but I find it helpful to realize that the entire point all all that was just to say that Bob essentially switches between the two states every time it's his turn, (by phasing out one set of Rotlung Reanimators and Xathrid Necromancers, and phasing in another set) so if Alice cycles cards in her Library she can switch her actions into or out of phase with Bob, so different things happen when a different set of infrastructure creatures are phased in.

- Haha, I'm guessing Lhurgoyf and Rat were chosen as end-of-tape markers for the L and R in their names?

- That was great. I love that the creature type representing a halt is Assassin.

Probability of Precipitation

Epistemic status: A definition I just learned, a preference statement, and some speculation

Yesterday I discovered that weather forecast probabilities aren't just the probability of rain in the forecast area, but also the probability that you'll be in a part of the forecast area where it's raining.

The National Weather Service defines the probability of precipitation (PoP) as:

PoP = C x A where "C" = the confidence that precipitation will occur somewhere in the forecast area, and where "A" = the percent of the area that will receive measurable precipitation (greater than or equal to 0.01"), if it occurs at all.

For example, if a meteorologist is 80% confident that at least 50% of the forecast area will see measurable precipitation then the PoP would be 40% (0.8 x 0.5 = 0.4 or 40%).

I have two thoughts about this right now:

First, I would strongly prefer they report these two numbers separately, so I can tell how much each factor is affecting the probability, and perhaps learn the parameter A over time myself from data. Hey, there's a good idea for a meta-weather app, if anyone wants to implement it.

Second, this might help explain something I've been wondering about: Why, when my weather app says there's a 20% chance of rain, does it always rain? It just seems very poorly calibrated. Since the geographic distribution of precipitation is uneven for various reasons, I may just be in a slice of the coverage area for predictions where it rains more often, and the PoP is being diluted by neighboring dry areas. Maybe. It's also possible I look at my weather app more often when it's more likely to rain (I dunno, maybe it smells different or something). Or perhaps I only remember instances when the app has predicted 20% and it rained anyway, because I got wet. I'd have to be a bit more careful to measure and record evenly if I really wanted to find out.

What to do with a new brain

I bought a Purple mattress about a month and a half ago, and it's been genuinely life-changing. I use Sleep Cycle to track things about my sleep. Before the mattress, I had gotten on the order of ~two 100% quality scores ever. Now I get 95-100% every night that something else doesn't wake me up (for instance, a crying baby). More to the point, I'm smart again. What should I do with that?

- I've got seven books I want to finish (re)reading: Apollo's Arrow, The Book of Why, A Programmer's Introduction to Mathematics, How to Measure Anything, An Elegant Puzzle, Zero to Sold, and Warranted Christian Belief.

- Apart from books I could finish in a few days, I'd also like to make progress in the Feynman Lectures on Physics, and Probability Theory: The Logic of Science.

- I'm restarting Journal Club at Decipher post-holidays, and the February paper is Magic: The Gathering is Turing Complete.

- I'm doing more blogging (like this post) for the all-comments-public experiment.

- I'd like to write a little game that helps with internalizing probability theory, and I was reminded by a friend recently that PICO-8 programming is a blast.

- I'd like to write a practical book on probability theory that normal people will find useful.

- I've got a hypothetical future company to work on designing.

- I'm also playing several games off and on: CrossCode, Hades, maybe Stellaris with some friends.

Just thinking out loud. There are a lot of wonderful options.

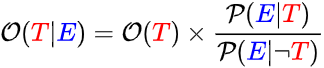

The Equation of Knowledge

There is an equation in probability theory that neatly encapsulates the ideal way to update your beliefs in the presence of evidence. It's called Bayes Theorem, and if you can bear with me for a bit, I promise this will be worth your time. I'll also make sure you can handle it even if you think you're "not a math person".

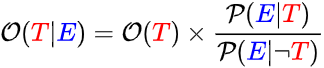

This is Bayes Theorem (odds form):

DON'T PANIC!

First off, the letters T and E that I colored red and blue stand for theory and evidence. Those aren't numbers, they're statements, such as T="The sky is blue", E="It looks blue when I look up".

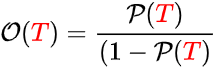

The fancy letter O hugging a theory T in parentheses is the odds of your theory T. (Yes, "odds" is singular...) It's any positive number, like 10, but people often say that as "10 to 1" for reasons I'll explain in a second. You read the following as "the odds of T".

Fancy P hugging a theory T in parentheses is the probability of your theory T. It's any number between 0 and 1 (or perhaps more familiarly, any number between 0% and 100%, which is the same thing). You read the following as "the probability of T".

Odds and probability are two sides of the same coin; I'm really only introducing two different forms of one thing. The odds for a theory is equal to the probability for that theory divided by one minus the probability for that theory.

You've seen this before, when people say the odds for something are "50/50", they're saying that the probability is 50%, so the odds are 50%/(100%-50%), which is 50%/50%. If they say the odds are "80/20", they mean the probability is 80%, so the odds are 80%/(100%-80%), which is 80%/20%. Sometimes people write odds with a colon, like 80:20, but that's just another way of saying 80/20. You're also allowed to reduce this fraction, because odds of 80/20 = 8/2 = 4/1. They're all the same odds, so express it in a way that makes sense to you.

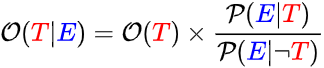

Back to Bayes Theorem. Here it is again.

There are two other weird bits of notation in here, the vertical pipe "|" inside some of the odds and probability parentheses, and this strange symbol "¬" in the lower right.

The vertical pipe "|" inside the parentheses is read as "given", and I want you to think of it as "when we imagine we're in a universe where this other statement has been observed to be true". So the following means, "The odds of the theory T when we imagine we're in the universe where evidence E has been observed to be true":

I hope this essay just got really interesting to you, because that kind of statement is something we likely really want to know every day of our lives. What are the odds of something I care about, given evidence of some kind? And there's an equals sign after it... There's an equation for that? Yes there is. No joke.

(Anyway, as an aside, when I said "imagine we're in a universe" above, I didn't mean to imply that we are not in that universe where we've observed evidence E. We might be. But we also might not be, and it's important for us to be able to leave things open until we've finished the calculation, and even after that it's important to keep an open mind, because it's easy to be fooled, either by others, or by ourselves, or by chance.)

The other strange symbol "¬" is read as "not", or "false", or "it's not true that", or "imagine we're in a universe where this thing is not true", or "imagine we have observed the absence of some evidence". The following would represent the odds that a theory T is false.

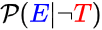

And this reads as "the probability that we would see evidence E given that we're in a universe where T is false" (which appears in the lower-right of Bayes Theorem).

Back to Bayes Theorem again. You now have all the tools you need to understand this.

To help chunk this together in your mind, we'll label O(T) as your "prior odds", i.e., your odds for T before you saw evidence, and we'll label the division happening on the far right as a "likelihood ratio".

Bayes Theorem then simply states, "the odds of a theory T, given that we observe evidence E, is equal to our "prior odds" times the "likelihood ratio" for that evidence.

The likelihood ratio is the balance between the probabilities of seeing evidence in two different universes, one where T is true, and one where T is false (i.e., ¬T). If the probability of seeing evidence E is higher in a universe where your theory T is true than in one where it's false, your odds should go up after seeing that evidence. Otherwise, they should go down.

Pause to consider how profound it is that this equation fully captures the ideal nature of evidence and its effect on our beliefs. If you observe some evidence E, it affects your confidence in theory T in proportion to how selective that evidence is for your theory.

If that evidence pretty much only ever appears in universes where your theory is true, then seeing it is very strong evidence for your theory. The likelihood ratio is very high. If on the other hand, some evidence E is exactly as likely in universes where your theory is true as when it's false, then E doesn't change your prior odds at all. In that case the likelihood ratio is just 1, and anything multiplied by 1 is itself. Finally, if some evidence E is unlikely when your theory T is true, then seeing E is evidence against your theory. The likelihood ratio in that case is less than one, so multiplying it by your prior odds gives you a number smaller than your prior odds.

At this point, I wonder if you're wondering if you can trust this equation. I presented it as a fait accompli, and although I'm sure it seems reasonable to you in a way, perhaps you have questions. Where did it even come from? Is it merely someone's opinion, expressed as an equation? And what about all the other things that affect whether we believe something or not, such as whether we're suspicious of the source reporting the evidence to us, or how confident we were in our own prior and evidence gathering in the first place? What about the weight of authority, and what about faith?

More on these later. Let it suffice for now to say that you should try expressing each of those things in the language of Bayes Theorem, and see if you still have objections after that. The field of Probability Theory (of which Bayes Theorem is a... theorem) is all about modeling uncertainty in degrees of belief, so questions of suspicion and trust fit right in. But you can count on reading more about this later, since it's one of my primary research interests.

I'm also going to save the life lessons this equation teaches us for future posts, to keep this one lean. Stay tuned!

Monte Hall

I was going to go to bed early today, but then I thought of a relatively clear explanation of the Monte Hall problem for those who have grokked the Play-Doh analogy of probability mass, i.e. that you've only got a fixed amount to dole out, and you must dole it all out.

The Monte Hall problem goes like this: Monte Hall presents you with three doors. Behind one of them is a shiny new car, and behind the other two are goats. You are invited to pick a door, with the understanding that if you pick the door with the car behind it, you keep the car. You accept, and pick a door. Monte Hall then opens one of the doors you didn't pick, revealing a goat, and he now asks you if you want to switch to the other unopened door, or stick with your original choice. What do you do?

Now, if you're familiar with this problem, you'll know that, counterintuitively, you should always switch to have the best chance of getting the car. Or if you're really familiar with the problem, you'll know that the correct answer depends very much on what rule Monte Hall is following when he picks a door. On the actual game show this came from, his decision rules are thus:

- He never opens the door you picked.

- He never opens the door with the car.

It's clear enough that when you originally picked your door, you had a 1/3 chance of picking the car, and a 2/3 chance of picking one of the goats. In the Play-Doh analogy, this means you've got 1/3 of your Play-Doh on each door. If Monte Hall follows the two rules above when he opens a door and reveals a goat, then the salient fact to which I'd like to call your attention is that he hasn't given you any new information about the door you picked, but he has given you new information about the other door he didn't open.

Regarding your Play-Doh:

- You have to move it off the door he opened, since there's no longer any chance the car is there

- You can't move it to the door you already picked because he hasn't given you any new information about the door you already picked.

To see that he hasn't given you any new information about the door you picked, consider first the probability that he opens a door with a goat if you picked the car. That probability is 100%. Both doors his decision rules allow him to pick hide goats. Now consider the probability that he opens a door with a goat if you instead originally picked a goat door. It's still 100%, because there's still always one door you didn't pick that contains the other goat. Whichever world you're in, he still opens a door with a goat, so it can't be evidence for or against the car being behind the door you picked. In other words, you still think the door you're sitting on has a 1/3 chance of hiding the car.

But if Monte Hall just forced you to move Play-Doh off of the door he opened, and you can't move it to the door you originally picked, the only place for it to go is to the other door neither of you picked. Which means that door now has twice the Play-Doh on it that you've got on your current door, so you should switch to it.

The reason that feels strange to people is that Monte Hall clearly didn't give you any evidence allowing you to update your probability assignment to the door you originally picked, so it feels like he didn't give you any information at all. But that's false. He implicitly gave you evidence about the remaining unopened door.

If you're having fun, let's take this further. I mentioned that his decision rules are crucial to the question we're considering, so let's weaken them separately to see what effect that has.

First imagine that he's allowed to open the door you picked, but he still never opens the door with the car. The observed data is also still the same; he opens one of the other doors, revealing a goat. Following the same line of thought from earlier, we need our two conditional probabilities:

- The probability he would open a door with a goat if you're sitting on the car door is now 100%, because he has plenty of goat doors to choose from that are not the car.

- The probability he would open a door with a goat if you're sitting on a goat door, however, is 50%. Remember we said he's willing to open your door, as long as it's not the car.

Because these two probabilities are different, the likelihood ratio between them is no longer 1:1 (it's now 1:1/2), so he has given you some information specifically about the door you picked, so some Play-Doh will move to or from that door, so the earlier argument no longer works. (In fact, under these new decision rules and observation, there's no reason to switch. An equal amount of probability mass ends up on your door and the other unopened door.)

Next, imagine that he's allowed to open the door with the car, but he'll still never open the door you picked. He still actually ends up opening one of the doors you didn't pick, and it's still a goat. Again following the same line of thought from earlier:

- The probability he would open a door with a goat if you're sitting on the car door is 100%. The two doors he's allowed to pick both hide goats.

- The probability he would open a door with a goat if you're sitting on a goat door is 50% like in the last analysis, but this time for a different reason: In this scenario he's not willing to open your door, but the two doors he's allowed to pick contain a goat and a car, so it's 50% he'll open the goat door.

Again, the probabilities are different, so the likelihood ratio between them is not 1:1, so the original argument doesn't work. He has still revealed equal information about the door you picked, and the final remaining door, and the result is equivocal.

All comments public?

I'm considering a trial-run of a strong bias towards discussion in public channels. That is, instead of having high-effort private conversations that evaporate as soon as they scroll off the screen, I'd invest that same high-effort in conversations (that I can't really avoid exerting anyway) into public Slack channels, Twitter, this blog, etc. I hypothesize that this would be more efficient with my time and effort. I can make more of a dent in the world.

To avoid spending much higher effort than usual, I'll need to stick to forums where I don't have to polish my communication much more than I already do. This blog seems like a pretty good place for that kind of thing, given its title.

How more content can be better than less... maybe

Had a new thought on this today...

Context: I dumped way too much text on a coworker, and I'm sure it's too much to process in a single conversation. But that's sort of how conversations should work, if there's going to be synergy: You need to to be able to let your brain go as far as it can before getting more input from others. And yet, if you do that, your conversation partner is overwhelmed.

- Thought: Perhaps the protocol should be

- A sends wall of text that represents all of the things A's thinking about

- B highlights bits for follow-up, for any reason, which are immediately visible to A

- While A is pondering why those highlights, B writes something about each one - questions, comments, objections. Each of these may themselves be walls of text, ('cause who says your reaction to something will always be simple?) which then follow the protocol recursively.

- The highlight thing seems important to me, and would need tool support (?). That's the main thought. I can understand a wall of text from you if I can highlight all the things that "catch" in my mind, and when I'm done, that's a TODO list for me.

More content shouldn’t be worse than less

I’ve been thinking about how [friend]'s info dumps just get ignored, but if he provided less up-front information, people would engage.

Also, when I send emails, detailing the whole problem guarantees the email won’t get read.

Also, recommending someone a whole book on something is worse than a blog post, is worse than a tweet.

This shouldn’t be so for me. If I want information on something, then a book should be better than a blog post, even if I don’t have time to read the whole book cover-to-cover. A whole book contains the information I need, and I need to get away from my fear of a wall of text.

As of now, all content lengths are equally usable. I’ll get good at x-raying the longer stuff. I'm already pretty practiced at this, but I want it to be second-nature.

Life lesson from AlphaGo

The researchers building AlphaGo first trained a neural network to accurately reproduce the move an expert human would make for a given board state. The neural network didn't end up being a great player, and lost half it's games against the runner-up AIs. Why? Because its goal had been to accurately reproduce the movements it had learned, instead of the actual goal of winning. Have you heard the term cargo-culting? That's what it was doing: merely going through the motions it had seen, without understanding why and using that knowledge to pull its bag of great moves together into an actual strategy.

Just like how most students sit in class and do their homework because that's what they're expected to do, accurately reproducing their role, and never once thinking about what it would take for them to actually absorb the material and make it a part of themselves. Or how everyone is really impressed with a small set of famous people, and then just go right back to the usual motions of their daily lives, without once trying to work out the path through action-space that would lead to their own ascendency.

That neural net got to winning 85% of its games against the runner-up AI when they further trained it using Reinforcement Learning to just flipping win any way it could.

So don't merely do what others do. Sample and remix what others do to win.

Evolve Bamboo One

After much agonizing and some budgeting, I bought an Evolve Bamboo One, and it came yesterday!

It was dark out when the board arrived and I was afraid of riding it for the first time near where I live (too hilly, some traffic, dark), so I only rode it down the hallway of my apartment... Ahem.

But today... Today I took it out to the nearby metro parking lot, which is quite empty and free over the weekend. It also has this great little hill for experimentation. I rode it for three hours up and down the hill before I started getting the 10% battery warning.

So fun. I love this thing. Good job, Evolve. 👍

My wife has named it "Tom", because I suggested "TOB" ("The One Board" [To Rule Them All]), and it sounded like I was saying "Tom" with a cold. Tom it is.

In case anyone is worried about me riding this thing, rest assured that I too am quite frightened of wiping out or getting hit by a car, so I'm taking every precaution. At the moment that's a helmet, a lot of practice with manual emergency stops, defensive driving, and a habit of hand signals, but I've also ordered a trigger guard for the controller and some wrist guards. I should also mention that it feels a lot safer than my normal longboard because it has brakes with which I can keep the speed down to where I feel comfortable foot-braking in case something goes wrong. There's also enough resistance from the motor that it's easier to keep my speed down without power.

Correcting for bias when estimating from evidence

Intuition patch

1. Base rate

2. Your guess

3. Est. correlation b/w evidence & outcome

4. Deviate #1 -> #2 proportional to #3.

Kahneman, TFAS

1. Base rate

2. Your guess

3. Est. correlation b/w evidence & outcome

4. Deviate #1 -> #2 proportional to #3.

Kahneman, TFAS

This is a tweet-packed nugget of wisdom from Thinking, Fast and Slow.

I love this book because it not only talks about what the evidence shows about our cognitive biases, but also what it says about how to correct for them, and how effective this correction can be.

What this^ bit is saying is that our guesses are largely based on substitution and intensity matching, which are great heuristics, but systematically biased to ignore regression towards the mean. That is, as he says frequently, we tend to assume that What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI), when there's actually a lot of hidden factors that can influence the outcome other than the evidence we've seen.

So, when asked to estimate the college GPA of a child who could read by the age of 4, we first do substitution ("estimate future GPA" -> "estimate precocity"), then intensity matching ("quite precocious" -> ~3.7 GPA), and stop there.

Kahneman suggests a way to approximate the outcome of an actual statistical analysis by adding in two more things: The base rate (in this case average) GPA of any student, without any extra information about them, and our estimate of the correlation between precocity and GPA. You start by assuming the student is merely average, and then you walk in the direction of your intuitive number you got (~3.7) a distance proportional to how correlated you think GPA is to childhood precocity.

Successful Scheduling System

Most successful scheduling system to-date:

I divided each day up into four chunks:

- Morning (10-12),

- Early Afternoon (12-3),

- Late Afternoon (3-6), and

- Evening (6-9).

Then I put tasks into one of three categories:

- Small,

- Medium, and

- Large,

where there are

- several (~4-5) Small tasks to a Medium,

- two Mediums to a Large, and

- only one Large task fits in one of the ~3-hour time-slots.

Take a break after every significant thing.

My Old Blog

I just found my old blog, archived in the Wayback Machine. Love that thing.

Greedy for beauty, longing never satisfied

I'm writing this now because, as I often mention, I get reset every morning. Regardless of what went on the day before, I always wake up a new person - sometimes happy, usually neutral leaning towards cynical, and sometimes nasty. I want tomorrow to be different, because today was so good. Today I know God is real and working out a grand plan. Today it started with music.

There's an amazing song arranged by Jon Schmidt called "Love Story meets Viva la Vida" because it's Jon on the Piano and some other guy on the cello first playing Taylor Swift's Love Story and then transitioning seamlessly into Viva la Vida. It stirs my soul, and alters my mood for the better, casting a generally deep and intriguing atmosphere over all of my thoughts. The song seems to subliminally encourage me to look deeper into thoughts, feelings and events, and I actually listened to it while I got caught up in my Bible reading.

The day before I had received The Weight of Glory, by C.S. Lewis, and started reading the title essay before going to sleep. I got about a third of the way through, and a couple of concepts hit me. I was affected most deeply by the idea that longing and the apprehension of beauty are very closely related, if not the same emotion. The concept resonates with the core of me for two reasons.

First, as Lewis mentions, that fact is good evidence that there is a Heaven, and that God is there. We experience longing when we see something beautiful because we have a sort of residual understanding, unmarred by the fall, that there is a place we haven't yet been, that we have been searching for all our lives; that there is something (Someone), some source, from which all the beauty we see with our eyes comes, and to which all that beauty points. This is far better to me than any alternate explanation of our feelings of beauty and longing in response to the beautiful, which is important for my peace of mind.

Second, I am also gripped by the concept because it seems so very real. I have been consciously keeping an eye out for months for something that I could hold onto - something that would be sufficiently ubiquitous in my daily experience to hold me close to God even when I didn't directly feel his presence. The fact that beauty is longing screams to me that there is a whole other class of beauty out there somewhere, of which the earthly beauty I see everywhere is but a mere suggestion.

C.S. Lewis also elaborates on the nature of that longing. When I listen to my beautiful music, I want to just dive into it. I want to eat it, become one with it, swish my feet around in it and then slide my whole body in. When I see a beautiful sunset, or the aftermath on a berry-bush of an ice storm, or the red and yellow autumn leaves, contrary to all worldly reason I desire - so badly it hurts - to join myself to that glory. Those desires are not satisfiable in this world, so why are they there? God loves us, and created us to worship him with our whole being forever. This is the greatest satisfaction we can attain, and is far more satisfying than anything we have ever yet experienced. And now one huge piece of evidence for it is felt in my bones, and surrounds me on every side.

"Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!"

[This essay first posted while at Cornell, around 2009.]

The Bible is God's Word. Read it!

[I just found this tucked away in the old Cru Cornell blog archive, and thought I'd repost.]

This blog post and subsequent 5-Minute Senior Message Brain Dump brought to you by:

- Petunia: A book I read in elementary school about this goose who thinks she’s wise because she found a book and carries it around under her arm.

- Pastor John of KCCE: "If you have never read all the way through the Bible, most of what you believe is lies." I’ll elaborate on that.

- How messed up I get when I don’t read what God wrote me for a long time. I’m a completely different person when I read (and internalize) my Bible in the morning.

- The Bible itself, for example Psalm 1 and John 15.

- The realization that if I don’t read my Bible, everybody and everything else in the world has a say in what I think except God. My classmates, TV shows, movies, my textbooks, magazine articles… all tell me explicitly or implicitly what’s important and worth-living for. They all lie. Only God doesn’t.

- The fact that the Bible gets more and more interesting and exciting the more you read of it, and the more you dig it up from the swamp of Christian cliches, "holy-speak" and cultural confusion.

The Bible is God’s word - whatever that means. I don’t mean to be irreverent. I say that because I think we Christians have created a class of words and phrases that we say and sing but never use in our every day lives, so we’ve forgotten what they mean. This phrase is important, so I’m gonna just say it over and over again:

- The Bible is God’s WORD. That is, in much the same way that Runaway Jury is John Grisham’s word, Harry Potter is J.K. Rowling’s word, Webster’s Dictionary was originally Noah Webster’s word, and Chemical Reaction Engineering is Octave Levenspiel’s word (no joke, that’s actually his name), the Bible is God’s. He has very intentionally written down what he thinks we need to know. He’s also written down a lot of things we’d really like to know, especially regarding his motives. He’s also written it down in such a way that we can find it interesting, assuming we’re not just complete bums.

- The Bible is God’s WORD (in response to your prayers). I wish God would just thunder answers to my prayers out of the sky, or skype me or something, but that’s just not how it works. That’s never been how it’s worked for most people, by the way. I may envy the Jesus’ disciples for being able to get straight answers out of Jesus directly (har har har), or Moses for being able to ring him up whenever he wanted, but for the vast majority of Israelites and us Christians, we will have to wait until death or the return of Jesus to talk with him face to face. There has always been a mediator. This is the way it works right now: you pray to God, and God really truly speaks to you by the Holy Spirit in the Bible with what you really need to hear. Don’t take this the wrong way, but it’s like you’ve got a chunk of God inside you doing the speaking, and the words he uses are those of the Bible.

- The Bible is GOD’s word. God is much cooler than those people I just mentioned. God (via Jesus), using whatever method, created the entire universe and everything in it. He cursed the world when Adam sinned. He did countless miracles and redeemed us from that curse, and Jesus took the throne after returning from the dead. He’s the most interesting person who has ever lived, and he wrote about it in the Bible.

- The Bible is God’s (THE HOLY SPIRIT’S) word. Not only did God write the Bible using Holy-Spirit-indwelt people so it doesn’t err, but he gives the Holy Spirit to Christians (among other reasons) so that we can understand the thing, so we will actually apply it to our lives (instead of letting it go in one… ear and out the other), and so it can be more than just "not boring". The Holy Spirit, through the Bible, gives us understanding of who God is. There is nothing better than that. Nothing God has created is better than himself, or more satisfying to the human soul. He made it that way.

I really wanted to excite you all about reading your Bibles, but so far all I’ve done is brow-beat you with a few good reasons why you should. It has been immensely helpful to me in the past few years to get concrete examples of God’s awesomeness in the Bible, so let’s just look quickly at two situations Jesus was in that we can all relate to - someone wanting to know about salvation, and someone trying to trap us in our words: (lots of my progression here ripped off from Michael Ramsden)

First example: [From Mark 10:17] "Good teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?"

GOOD QUESTION. What would you say if some classmate of yours came up to you and asked what he should do to inherit eternal life? First, how would you feel? WIN. Best day ever. Of course you would say, "Why, my dear friend, in order to inherit eternal life ye must repent of thy sins and vouchsafe thy soul unto the Lord Jesus." When someone asked this question of Jesus, he said, "Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone," and then essentially, "follow the ten commandments stupid." Then the guy says he’s kept the commandments, and Jesus pities him and throws him a bone: "You lack one thing: go, sell all that you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me."

What’s going on? Doesn’t Jesus understand the gospel? To make a long story short, yes. But he knows this guy is all mixed up. What must I DO could either be a sincere attempt to follow Jesus at all costs, or it could be a confused request for a way to earn his own salvation, and Jesus knows which it is. Jesus’ answer is therefor really cool: "Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone." "Good teacher, what must I do…" held within it an implicit assumption that this guy could make himself good enough to inherit eternal life. But if you must be good to go to heaven and God alone is good, then who is going? No one. In other words, this guy’s application to join the Trinity has been denied. He does not meet minimum entry requirements.

My point is, Jesus answers people right where they are with exactly the answer/question they need. There’s actually another instance in the gospels where Jesus is asked almost exactly the same question and he answers completely differently. Sometimes he’s harsh, sometimes he’s gentle, but he’s always right on. His answers and counter-questions are always brilliant and I encourage you to go puzzle through them.

Second example: [from Mark 12:13-17] The Pharisees sent some people to trap Jesus in his words. (It explicitly says that, so we know what they say is to trap him…): "And they came and said to him, "Teacher, we know that you are true and do not care about anyone’s opinion. For you are not swayed by appearances, but truly teach the way of God. Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not? Should we pay them, or should we not?" Does anyone see the trap? Does anyone understand the cultural context this comes out of?

Israel was under Roman rule. If you pay taxes to Caesar, you’re supporting the oppressors. That’s morally bad, and of course the Messiah isn’t going to morally compromise. But if you don’t pay taxes to Caesar and tell others not to, you’re definitely an insurrectionist and must be killed. Win-win for the Pharisees, or so they think. Jesus cannot answer "yes" or "no" to this yes-or-no question.

So he doesn’t. "But, knowing their hypocrisy, he said to them, ‘Why put me to the test? Bring me a denarius and let me look at it.’ And they brought one. And he said to them, 'Whose likeness and inscription is this?’ They said to him, 'Caesar’s.’ Jesus said to them, 'Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.’" And it says they marveled at him. Why did they do that? Because his answer was pure poetry, and in a very compact phrase, answered both "yes" and "no" where it counted. Essentially, "God owns you. Render to God what is his. And as for the tax? Yes pay it, but give God what he wants - your very selves."

Convinced? Then please start reading your Bible. Start anywhere, and read however much in a day you can stand at the stage you’re at, as long as that’s more than none. If you have a plan you just can’t seem to get into, throw it away and start a new one that you can get into. Here are ten different plans, each of which has its own features and heritage. Some are pretty normal, differing only in the particulars, and others are unusual (like the Chronological reading plan). Please do pick one and start it wherever you are in the year, if you’re not on one yet:

If you’re like me, though, and having to read a specific passage on a specific day stresses you out so much that getting behind is a death sentence to your reading for the rest of the month, I recommend something like this:

I don’t know who "Professor Grant Horner" is, and like Challies, I’m a bit wary of anything called a "Bible Reading System", but I like the theory and the bookmarks. Anyway, it’s just a set of ten bookmarks, each of which has a list of books on it. Theoretically, you read one chapter from each bookmark every day, and the bookmarks walk through the books on their list and then wrap around. You get to compare lots of Bible with lots of other Bible, and if you miss a day or two or want to read extra, there’s no penalty, not even a psychological one.

Unreliable idea handlers

It's difficult to tell, among all of the conflicting voices in the world, who is right. But some people are just agents of chaos in this endeavor: the ones who will present things they only just heard as facts, those who present as certainties those things of which they are actually uncertain, those who conflate the plausible and the probable, and those who just pick ideas off the ground and wear them unexamined.

Don't believe a word they say.

That said, I'm not actually sure what to do with them. I want to help them learn to care more about the difference between truth and rumor, but these people are often offended when I question their rigor. Let me know if you have any ideas.

The problem with believing you can figure anything out

The most important thing I learned from Cornell, something kneaded into me with every impossible assignment completed, was that nothing is actually beyond me. There's nothing too hard, too complicated, too esoteric or too impressive that I simply lack the capacity to understand. Such things don't exist.

"The secret things belong to the Lord our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever..."

- Deuteronomy 29:29

This realization, if worked into your bones and your knee-jerk reaction to new ideas, is a great blessing. Whole new worlds break open, and the quest for the key to the gate of each new kingdom just becomes a puzzle-hunt. There's also a bit of a curse, or perhaps just a new challenge:

Once there's nothing you feel you can't do, once the artificial barrier is removed, suddenly you have no barrier to dabbling in everything. I've started 14 books, I follow 77 blogs, there are 64 unread articles in my Instapaper inbox... It gets out of hand rather quickly.

I hypothesize that what I need is a new, better barrier, as well as a way to prune the system periodically. I'd definitely take suggestions though. Tweet @danielpcox to let me know what you think.