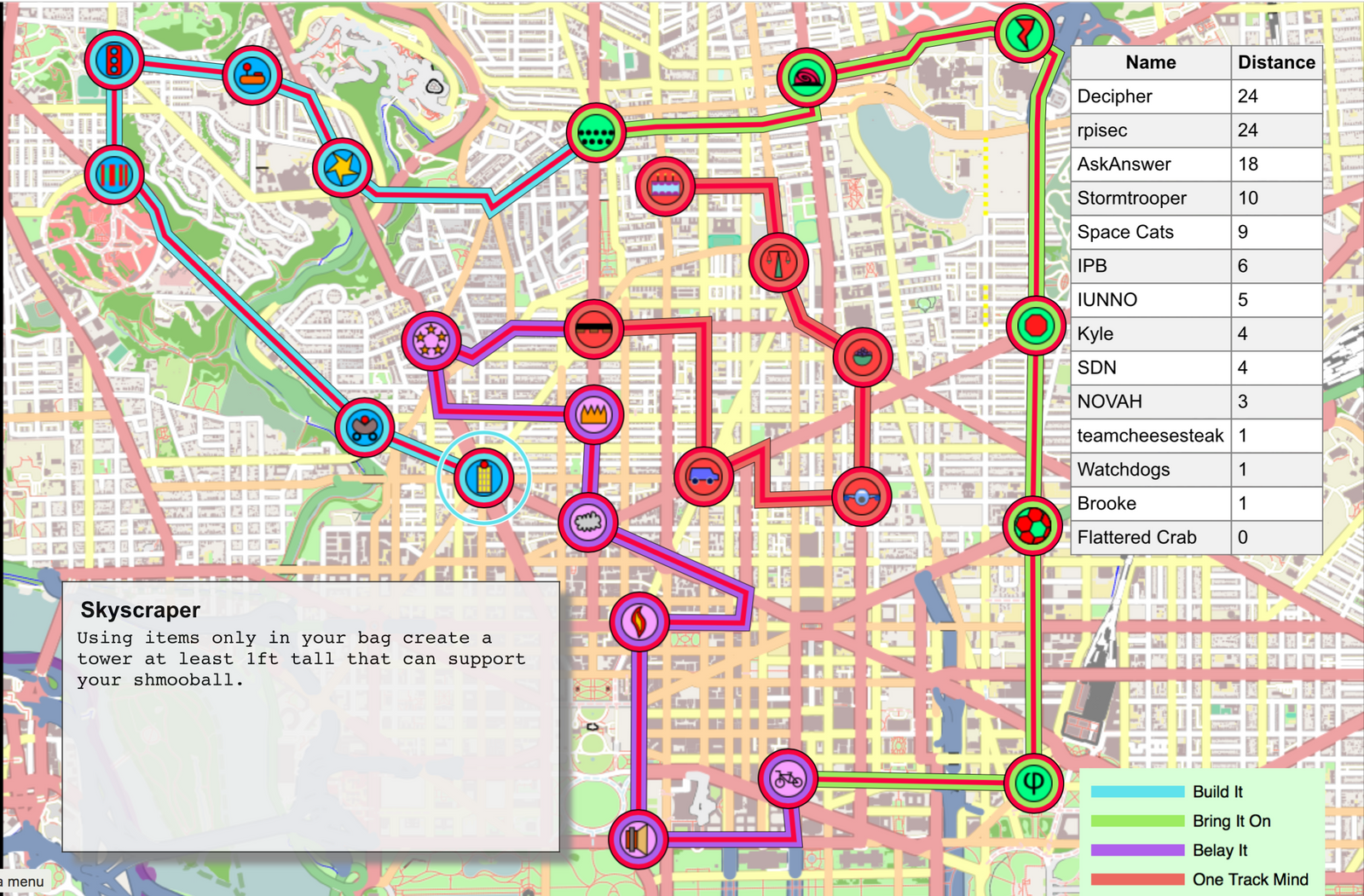

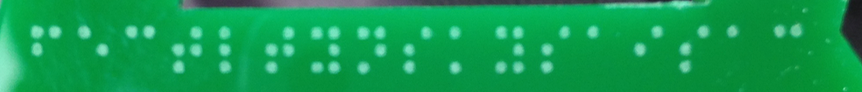

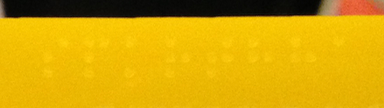

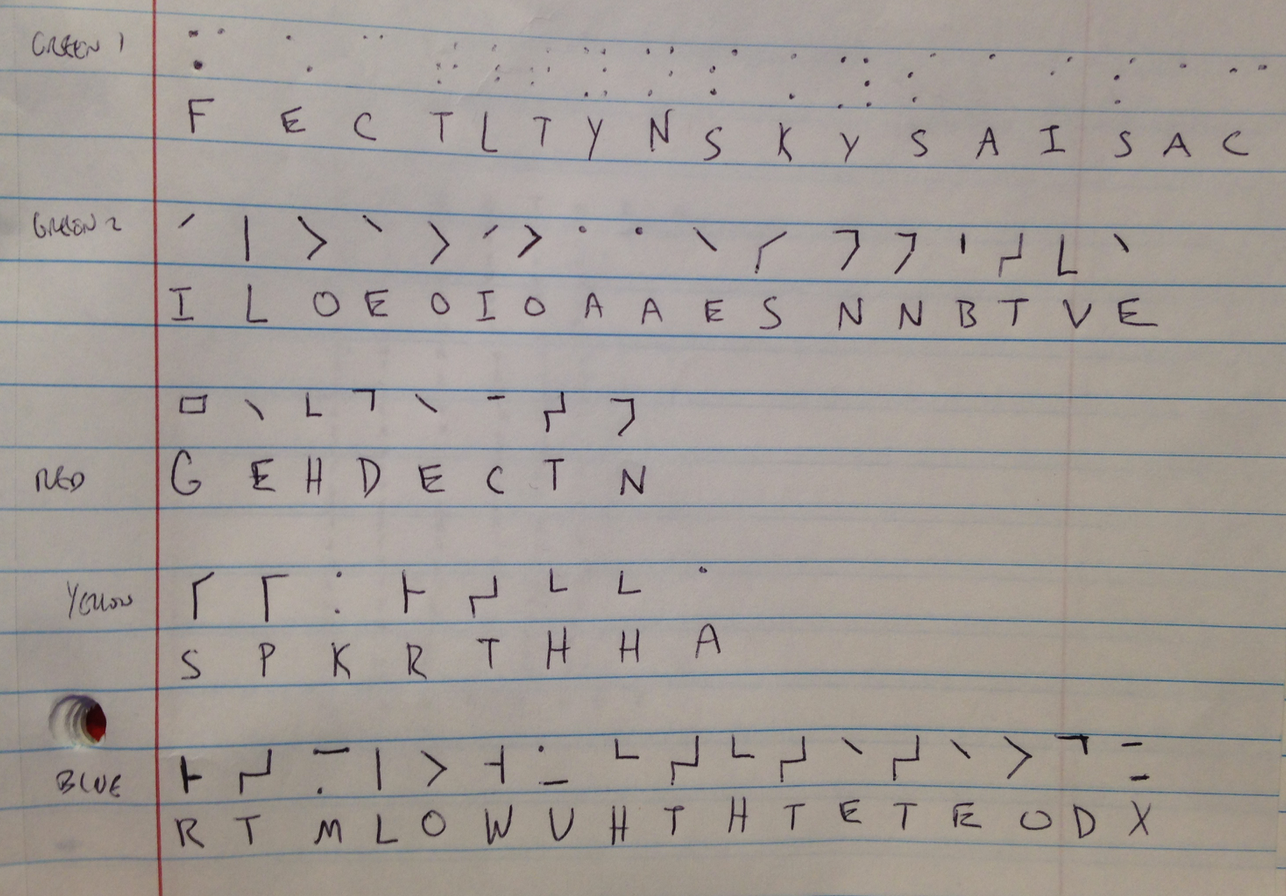

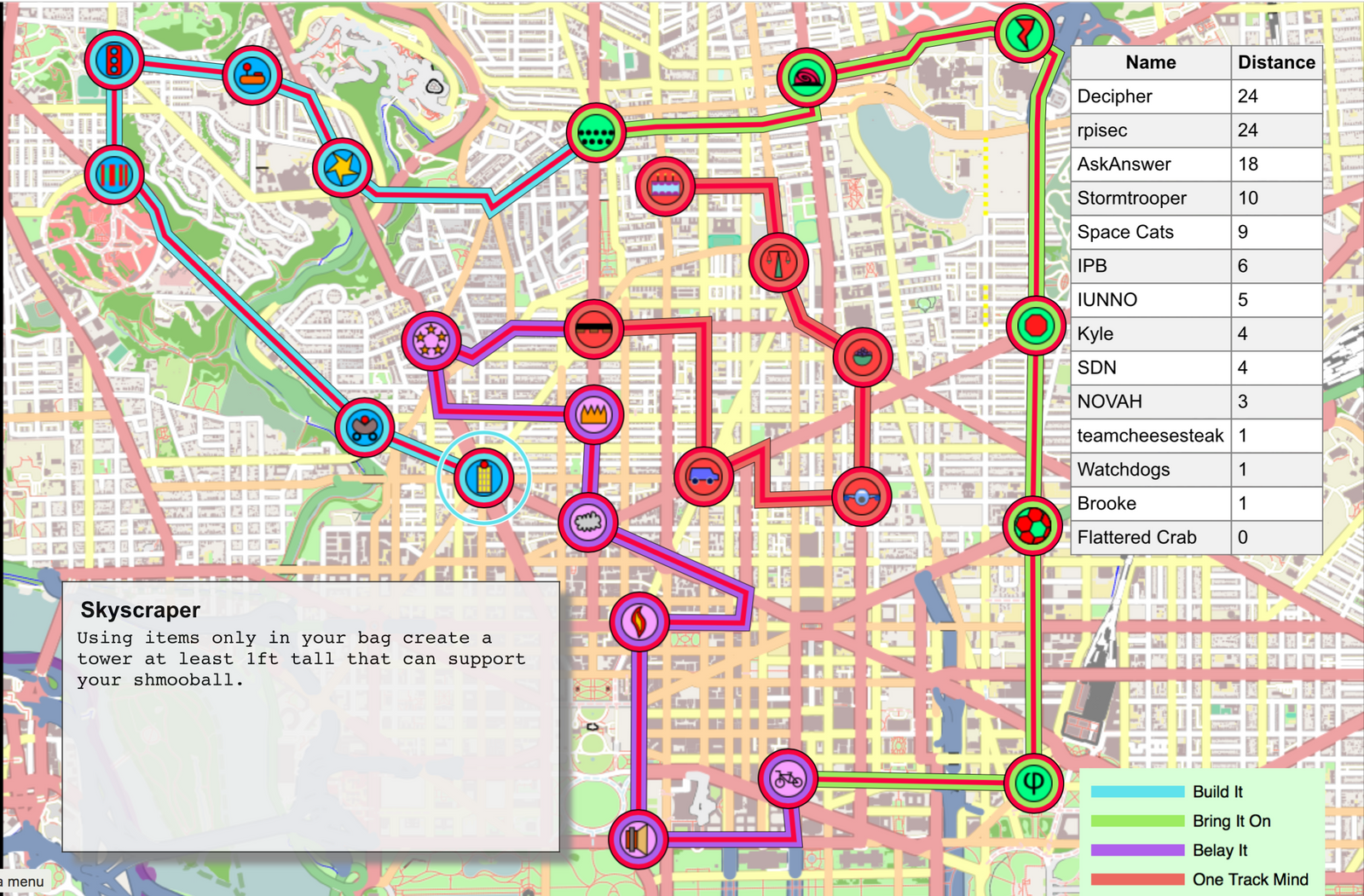

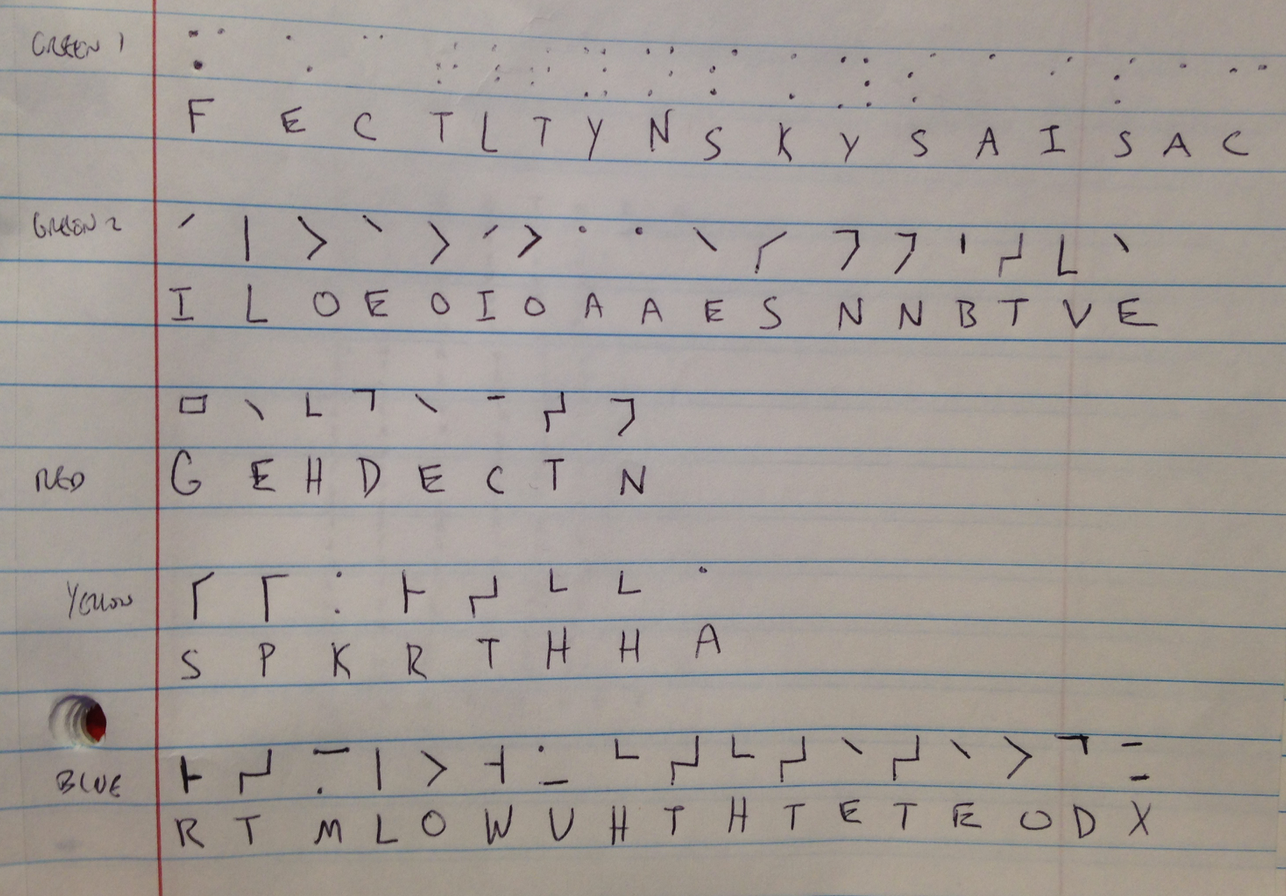

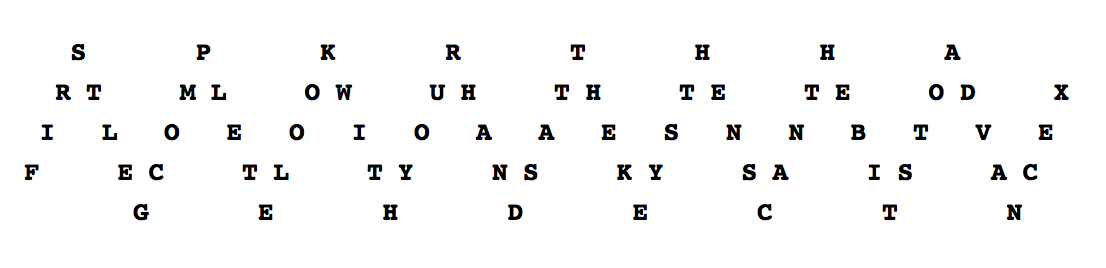

- Team Flowers By Irene, the organizers, for awesome puzzles and a sense of humor

- rpisec for being a worthy rival, and right there with us all the way to the end

- Decipher team for putting so much effort into this thing

The emergent picture of the Chief Figure in the campaign, so far from being that of a high-souled teacher patiently indoctrinating the multitudes with truths of timeless wisdom, is rather that of the Strong Son of God, armed with his Father’s power, spear-heading the attack against the devil and all his works, and calling men to decide on whose side of the battle they will be.A. M. Hunter, Introducing New Testament Theology

Does the Moral Law really have to have come from a personal being? Could it have evolved? If it serves some survival purpose, what is it?

Lewis also calls it the "rules of decent bahavior", which I like because it’s more descriptive and evokes the substance of the thing at a glance for me. The only survival advantage conferred by the rules of decent behavior is their contribution toward society, though they are imperfect at best at promoting society. (E.g., it might help society more if we simply executed all criminals, outlawed anything damaging to our health, and gave the former group’s property to proven contributors to society, but this would offend our sense of the moral law. Or am I just arguing from my own revulsion at that idea, since it does seem pretty common for people to believe in the greater value of people who contribute to society - their lives are considered to be worth more than others?)

Lewis is mostly talking about "oughts". You ought not to move my stuff and take my seat in a crowded theater when my back is turned. If anyone thinks that’s right, they feel compelled to explain why the usual rules don’t apply there, which is to acknowledge their existence. (Interesting that we also have a sense of the ways in which the rules might be suspended.) So can there be oughts without God? My knee-jerk reaction is to say yes, because oughts might just be part of a system evolved in us to promote the good of society, which is ultimately better at keeping our genes around than the alternatives. Groups of humans that cohere form civilized societies, and groups are better at survival.

One might ask at this point whether this argument isn’t too strong: Why don’t we all have the same opinions about everything, then? We would certainly cohere a lot better if we didn’t disagree. I think the answer there is that diversity is also essential to surviving unexpected events, so any truly resilient solution would have to balance diversity and unity, and this, it is postulated, is the source of our common understanding of the rules of decent behavior.

Lewis may be oversimplifying the "herd instinct" as he calls it. Impulses are uncomplicated in his view. I’m not sure he’s wrong either. He says herd instinct tells you to do right by your neighbor, and is one of several instincts we have, but that the moral law cannot itself be any of these because it sits in judgement upon them. This is intriguing. He treats them as notes on a piano, and the moral law as advising the piano player. But what if the moral law is just a more complicated instinct? He says that it can’t be because it’s not consistent, so to speak: it doesn’t always advise the same notes to be played. In fact, any of them can be regarded as "bad" by the moral law, and any can be regarded as "good", depending on the circumstances. This, he says, shows that the moral law is not itself an instinct.

I’m not sure. People have tried to write down the rules it follows, and in fact, this is how we teach one another what morality is and how to live by it. It is true though that none of its codifications feel like they capture the whole thing, and those that feel like they capture it better seem a bit vague, or mysterious (e.g., the Sermon on the Mount).

I’m reminded here of an argument I make for why we perhaps should be able to discover the workings of our own consciousness: that God has no parts and we are created beings, so therefore there must have created us by some means, and therefore we ought to be able to discover them. The relevance for the current topic is that similarly, if we are actually capable of following the moral law, we ought to be able to write it down.

An argument I have against my argument above is a common one with me: we may be, loosely speaking, part of God’s imagination, and therefore we don’t actually have to follow discoverable rules, since he’s infinite and therefore necessarily largely undiscoverable. It therefore seems possible that the rules of our own consciousness and the rules of the moral law both belong to the wider world of God’s infinite understanding, and that the discoverable rules of the universe make up a finite subset of the rest of God’s mind.

Anyway, back to the question of whether the moral law could simply be some useful behavior for survival, and therefore no evidence of God’s hand on us. It seems suggestive that I feel like I can’t just throw off the question with an "of course". Why not? Just because morality seems elusive as well as common and clear? To summarize Lewis, we all find in ourselves a common understanding of the rules of decent behavior, even accounting for our variations on the subject and for the fact that we often break them and excuse ourselves, and that it can’t itself be merely due to the herd instinct because it sits in judgment of the herd instinct. (And all others, deciding which of our instincts prompts we ought to obey: "But feeling a desire to help is quite different from feeling that you ought to help whether you want to or not.")

More quotes:

"The Moral Law tells us which tune we have to play: our instincts are merely the keys."

"If two instincts are in conflict, and there is nothing in a creature’s mind except those two instincts, obviously the stronger of the two must win… But at those moments when we are most conscious of the Moral Law, it usually seems to be telling us to side with the weaker of the two impulses… And surely it often tells us to make the right impulse stronger than it naturally is? I mean, we often feel it our duty to stimulate the herd instinct, by waking up our imaginations and arousing our pity and so on, so as to get up enough steam for doing the right thing. But clearly we are not acting from instinct when we set about making an instinct stronger than it is."

"If the Moral Law was one of our instincts, we ought to be able to point to some one impulse inside us which was always what we call ‘good’, always in agreement with the rule of right behavior. But you cannot. There is none of our impulses which the Moral Law may not sometimes tell us to suppress, and none which it may not sometimes tell us to encourage… Think once again of a piano. It has not got two kinds of notes on it, the 'right’ notes and the 'wrong’ ones… The Moral Law is not any one instinct or set of instincts: it is something which makes a kind of tune (the tune we call goodness or right conduct) by directing the instincts."

But, I think to myself, what if the Moral Law is the instinct to bring up the tune, plus the tune itself, and the tune has been bred into us through natural selection? What if the tune is encoded in our DNA, and its particular pattern cultivated by mutation and natural selection to improve our chances and give us an edge over other species and the environment?

Firstly, evolutionary arguments are either too hard or too easy to make. It’s quite easy to say that the moral law must confer some survival advantage, but quite hard to explain how. The engineer in my says that you shouldn’t claim to understand something until you can build one yourself.

Secondly, is it explaining or explaining away the very strong feeling that something is really wrong (e.g. genocide)? And once we’ve made that argument, that we only think it’s wrong because, e.g, we’re on the whole averse to anything that would reduce the genetic diversity of the planet by so much, why do we largely disbelieve that that excuses us from following it? Materialists disbelieve in the evil of genocide, but feel very strongly compelled to make arguments against it on other grounds. I think this is double-talk: It’s not wrong (because there’s no such thing as right and wrong) but you shouldn’t do it anyway.

On that note, if Mind really is a fundamental thing about the Universe we live in, and not merely some late emerging property, how would we even go about convincing ourselves of it? Couldn’t we always come back to saying, "well, I just feel that way because I am a mind and naturally want to turn everything else into one."

At this point, it just seems more honest to me to say that the Moral Law and Mind in us really are pointers to something fundamental about the Universe. I can understand a distate for the thought, since it seems unapproachable in the way that we’ve grown used to approaching things since Science came on the scene. It also seems a bit inelegant once you’ve tasted the beauty of mathematics and physics. But when I’m not troubled by this, it’s because beauty itself is supposedly rooted in God, and a pointer to him.

To make that a bit more precise, God is simple. He has no parts. All that is good and right in the world is a projection into the finite and multidimensional what to him is infinite and singular. Hard to explain quite what I mean, but I’ve heard it said that we talk of God having characteristics and aspects like we seem to, but in actuality he is a single, simple… Someone. Elegant and beautiful not even at an extreme, but fundamentally. Elegance Himself.

When am I allowed to just give up and believe these things? I run myself around in circles, and even come back to the same conclusions again and again. God is who he is. Mind came before Universe. It’s just the best explanation in a world of uncertain explanations. Perhaps I distrust it because I feel like a creature of supernatural meaning and purpose, and the world feels created. Or perhaps I distrust it because I often feel like a meaningless, accidental creature in a cold mechanistic Universe.

{#"url-to-match.com" {:username "username" :password "password"}}

encrypt it with gpg,

gpg --default-recipient-self -e \

~/.lein/credentials.clj > ~/.lein/credentials.clj.gpg

delete the original,

rm ~/.lein/credentials.clj

and then refer to it in your project.clj like this:

:repositories [["releases" {:url "https://url-to-match.com/repository/internal"

:creds :gpg}]

["snapshots" {:url "https://url-to-match.com/repository/snapshots"

:creds :gpg]]

https://github.com/technomancy/leiningen/blob/master/doc/DEPLOY.md#gpg

I had a bit of trouble at first connecting to gpg-agent, but solved it by putting this in my shell startup script (~/.zshrc for me):

gpg-agent --daemon --enable-ssh-support \

--write-env-file "${HOME}/.gpg-agent-info"

if [ -f "${HOME}/.gpg-agent-info" ]; then

. "${HOME}/.gpg-agent-info"

export GPG_AGENT_INFO

export SSH_AUTH_SOCK

export SSH_AGENT_PID

fi

GPG_TTY=$(tty)

export GPG_TTY

There are two kinds of play, and both are important, but they exist in a tiny hierarchy of usefulness, and the lower kind of play is strictly less useful than the higher kind.

The lower kind of play is merely to recharge, and the activity itself doesn’t leave me enriched in any real-world way once I’ve disengaged. For me, video games and candy books (merely fun page-turners without insight or other take-aways) fall into this category. They’re _extremely useful_ for when I cannot make my mind focus,

The higher kind of play is still undirected and without deadlines, so it still _is_ play, but there are take-aways. A good example would be biographies, which are extremely entertaining to me, but also require more brain power than candy books. From biographies I take away inspiration and perhaps some advice in a useful form (demonstrated human behavior). Tinkering with electronics or software projects or _anything_ really that captures my curiosity leaves a residue of value after I’m done.

I think I should never engage in low play when I’m capable of high play, or I’m just wasting an investment. Time is precious, and play (both kinds) is important for maximizing it.

"There was no second chance. We all knew that," Hamilton said. "We took our work very seriously, but we were young, many of us in our 20s. Coming up with new ideas was an adventure. Dedication and commitment were a given. Mutual respect was across the board. Because software was a mystery, a black box, upper management gave us total freedom and trust. We had to find a way and we did. Looking back, we were the luckiest people in the world; there was no choice but to be pioneers; no time to be beginners." Hamilton’s integrity and ability to balance fearlessness with attention to detail may have ensured Apollo 11’s success.

I don’t know what a business is. All a company is is a bunch of people together to create a product or service. There’s no such thing as a business, just pursuit of a goal—a group of people pursuing a goal.Elon Musk

There is nothing that can be said by mathematical symbols and relations which cannot also be said by words. The converse, however, is false. Much that can be and is said by words cannot be put into equations – because it is nonsense.Clifford Truesdell

The pleasure of pride is like the pleasure of scratching. If there is an itch one does want to scratch; but it is much nicer to have neither the itch nor the scratch. As long as we have the itch of self-regard we shall want the pleasure of self-approval; but the happiest moments are those when we forget our precious selves and have neither but have everything else (God, our fellow humans, animals, the garden and the sky) instead…C. S. Lewis

Now I’m thinking about building it into my daily routine, and trying to remember to take brain-rest breaks whenever I feel harried.

Java is obsessed with objects, so if you want to manipulate some data you first create a data access object to represent it, fill it in, and then send it along the wire. Better still, you teach the object to serialize and deserialize itself, and now you can just interact with the data through Plain Old Java Objects!

Now some editorializing: That is completely insane.

Sure, if that’s what you’re used to, it will make more sense to you, but your data is data on both ends of this process, and there’s great effort in the middle to essentially create a little proprietary DSL with which to manipulate these DAOs. In other words, you’re doing unnecessary work to make it less generally accessible for the time while it’s being handled by your program. Why not just leave it as data, and manipulate it directly?

It’s a language thing. Object-oriented languages put heavy emphasis on objects, which are suitable for modeling components and processes, and a terrible for modeling data. Data-oriented languages (like Clojure) try to ensure whenever possible that data remains data, in a format common to practically all libraries. There isn’t a separate DSL for each type of datum, so you can reuse the same functions over and over again on all data that comes to you, easily and generically.

Lastly, I understand that the desire to transform data into objects also stems from the desire to strongly type data. This is understandable, but I beleive also misguided. The very reason we may feel the need to impose a type system upon data is that it didn’t contain the type information in the first place. Which means the data itself isn’t strongly typed when it comes in, and it isn’t strongly typed when it goes out. We should avoid pretending that it obeys a rigid model for the sake of API evolution and interoperability. There are other ways to do validation and coercion of data, and schemas aren’t just for object-oriented models.

Programming is 90% writing, and writing is rewriting.

Lately I haven’t been making good use of Things, because I had one week where my whole plan obsoleted by events, and I didn’t have time to go back through and adjust. I feel a second wind coming on though, and in fact, there’s a task in there now to "Make Things work for me".

As explained in What’s Best Next, I really need to pick a day of the week on which I go through my outstanding tasks and schedule them for days of the week, a "week planning session". Then I imagine that as new tasks enter my system, I can safely schedule all tasks that should be done soon to resurface on that day, and all other tasks don’t need to be scheduled at all (because I revisit them frequently anyway), but rather categoried for later consideration.

I also need to decide that "Things runs it all", and consult it frequently to know what comes next. This will validate the system, inculcate the habit, and ensure that my weekly scheduling work is actually valuable. I should make it a habit to complete all of the tasks in Today every day, or else reschedule them.

Lastly, I should ensure that my filing and categorization system in Things makes sense, and that I know when to peek in each box. I currently use Things as if the categories didn’t exist (like a flat list of tasks except for the schduling system), but it has support for Projects, Areas of Responsibilitiy, and tags, each of which can help me with different ways of knowing what to do and when once I have a weekly planning ritual in place.

Walt Whitman, Leaves of GrassABOARD at a ship’s helm, // A young steersman steering with care.

Through fog on a sea-coast dolefully ringing, // An ocean-bell-O a warning bell, rock’d by the waves.

O you give good notice indeed, you bell by the sea-reefs ringing, // Ringing, ringing, to warn the ship from its wreck-place.

For as on the alert O steersman, you mind the loud admonition, // The bows turn, the freighted ship tacking speeds away under her gray sails, // The beautiful and noble ship with all her precious wealth speeds away gayly and safe.

But O the ship, the immortal ship! O ship aboard the ship! // Ship of the body, ship of the soul, voyaging, voyaging, voyaging.

because of yesterday’s personal revelation (more on that some day) and quality survival time with katie playing Ark

and because i’m working on something interesting, i feel like my many responsibilities are now better organized and manageable, and because i’ve figured out how to be comfortable sitting

(a pretty helpful revelation i’ve had about myself recently is that i’m way more comfortable in shallow chairs with a cushion in back, both of which are achievable by putting a very thick cushion behind me while sitting in any chair, and kinda slouching a bit)

i often wonder if i should either pick something (emacs and intellij are both looking pretty good for this) that is just infinitely flexible, and so "settle down" into a pattern that embraces my desire to constantly tweak my system, or if i should just decide to live with a certain set of manual annoyances, and just pick a technology that makes 90% of my use-cases easy